|

Consumers’ desire for a healthier, more sustainable world has driven

even mainstream institutions to make major changes. Perhaps most

exciting, the business community is joining the effort to reduce global

warming and to implement more sustainable practices.

In May

2005, Jeffrey Immelt, the man who replaced Jack Welch at the helm of

General Electric (GE), stood with Jonathan Lash, the President of World

Resources Institute (WRI), a leading environmental organization, to

announce the creation of GE Ecomagination. The two co-authored an

article in The Washington Post titled, “The Courage to Develop

Clean Energy.”[1]

Immelt

committed GE, the sixth largest company in the world, and the only

company that would have been on the Fortune 500 list if it had existed

in 1900 and is still on it today, to implement aggressive plans to

reduce emission of GHGs, spending $1.5 billion a year on research in

cleaner technologies. As part of the initiative, Immelt promised to

double GE’s investment in environmental technologies to $1.5 billion by

2010, and reduce the company’s GHG emissions by 1% by 2012. Without any

action, GE’s emissions would have gone up 40%.[2]

GE’s

announcement was rapidly followed by an even more significant

environmental commitment from Wal-Mart, now considered the largest

company in the world. In 2006, Lee Scott, the CEO of Wal-Mart,

announced that his company would undertake a major effort to reduce its

emissions of GHGs. He set a goal of supplying his stores with 100%

renewable energy. Wal-Mart is experimenting with green roofs and green

energy (which is now used to power four Canadian stores, for a total of

39,000 megawatts—the single biggest purchase of renewable energy in

Canadian history). The company pledged to become the largest organic

retailer and to increase the efficiency of its vehicle fleet by 25% over

the next three years. It will eliminate 30% of the energy used in store

and invest $500 million in sustainability projects.[3]

An

unabashedly astonished article in the San Francisco Bay Guardian

reflected: "Wal-Mart’s rationale for all of this, of course, has absolutely

zero to do with any sort of deep concern for the planet (though it does

make for good PR), nothing at all about actual humanitarian beliefs or

honest emotion or spiritual reverence, and has absolutely everything to

do with the corporation's rabid manifesto: cost-cutting and profit."

The reason Scott promised that Wal-Mart will double the fuel

efficiency of their huge truck fleet within a decade? Not to save the

air, but to save $300 million in fuel costs per year. The reason they

aim to increase store efficiency and reduce greenhouse gasses by 20%

across all stores worldwide? To save money in heating and electrical

bills, and also to help lessen the impact of global warming, which is

indirectly causing more violent weather, which in turn endangers

production and delivery and Wal-Mart’s ability to, well, sell more

crap. Ah, capitalism.[4]

In

reviewing the leading business stories of the year 2006, columnist Joel

Makower, a veteran commentator on green issues wrote:

Two thousand six may be

the year that green business crossed the line from a movement to a

market. It was long in coming, of course, with several watershed

moments…In 2006, GE initiatives to harness "green” as an engine for

topline growth hit their stride… ahead of its plan to reach $20 billion

in annual sales of Ecomagination products by 2010.

Dupont launched its own

initiative, committing to $6 billion in new revenue from "business

offerings addressing safety, environment, energy, and climate

challenges.” Dow came on board with the aforementioned water initiative.

Carpet maker Interface introduced a consulting service to help

organizations as diverse as Sara Lee and NASA get their sustainability

programs off the ground. Caterpillar launched an ambitious business unit

to develop a remanufacturing industry in China. And a wide range of

innovators developed new, clean technologies for everything from bottles

to buildings to boats -- part of the year's overall boom in clean-tech

activity….

Shareholders --

specifically, large institutional investors like pension funds and

university endowments -- are emerging as the real power brokers in the

climate arena...

The leading investment

firms are jumping in, too. Merrill Lynch, for one, issued a report

profiling seven companies it believes are best positioned to capitalize

on what it calls the "clean car revolution." Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase,

and Morgan Stanley also published research reports analyzing the

financial performance of the carbon markets, sometimes identifying who's

naughty and nice -- that is, the leaders and laggards in their various

sectors.[5]

The

business community is actually often ahead of the government in being

willing to take an aggressive stance on protecting the climate. For

years, many American businesses succumbed to the concerted media

campaign claiming that taking action against global warming will harm

businesses and the economy.[6]

Now, business leaders are recognizing that, in fact, quite the opposite

is true: The conventional wisdom that businesses will oppose efforts to

implement programs to protect the environment is increasingly antiquated

thinking.

Many

business leaders see a need to abate climate change for moral reasons.

Lee Scott, CEO of Wal-Mart, stated in the pages of Fortune Magazine:

There can’t be anything good about putting all these chemicals in

the air. There can’t be anything good about the smog you see in

cities.

There can’t be anything good about putting chemicals in these rivers in

Third World countries

so that somebody can buy an item for less money in a developed country.

Those things are just inherently wrong, whether you are an

environmentalist or not.[7]

There

is an opportunity now to begin a new conversation between citizens, the

companies that deliver the services we all desire, and the government we

have empowered to set policy to achieve the sort of future we all

desire.

Companies often start a program of GHG reductions because they realize

that acting now is a “no regrets” strategy. If climate change turns out

to be real, they will already be in a leadership position by dealing

responsibly with it. Even if the scientists are wrong and there is no

threat to the climate, these are actions that a well-managed business

would want to take anyway, because doing so is profitable. Enormous

opportunities exist to reduce costs by reducing the energy they use to

run their operations. It just happens that this is exactly the same

strategy they would employ to reduce their GHG emissions.

There

is a very solid business case for such a position. Adopting an

aggressive program of GHG reductions can be highly profitable for

companies and cost-effective for non-profit (including government)

organizations.[8]

Reducing the amount of energy that a business uses reduces costs

and directly enhances a company’s bottom line. Failing to reduce energy

use, and tolerating carbon emissions as part of “business as usual” is

actually a high-risk strategy for a business or for a community.

Companies that reduce GHG emissions, especially in the context of a

broader whole-system corporate sustainability strategy, will achieve

multiple benefits for shareholders beyond reducing their contribution to

global climate change. Governments that take a similar course will

accrue similar benefits to their citizen stakeholders.[9]

These

benefits include:

-

Enhanced financial performance from

energy and materials cost savings in:

industrial processes;facilities design and

management;fleet management; andgovernment

operations.

Enhanced core

business value:sector performance

leadership;greater access to

capital;first mover

advantage;improved corporate

governance;the ability to drive

innovation and retain competitive advantage;enhanced reputation

and brand development;market share capture

and product differentiation;ability to attract

and retain the best talent;increased employee

productivity and health;improved

communication, creativity, and morale in the workplace;improved value chain

management; andbetter stakeholder

relations.

Reduced Risk:insurance access and

cost containment;legal compliance;ability to manage

exposure to increased carbon regulations;reduced shareholder

activism; andreduced risks of

exposure to higher carbon prices.

Leading

CEOs around the world know this. CEOs surveyed by the World Economic

Forum in Davos in 2000, stated that for them, “The greatest challenge

facing the world at the beginning of the 21st Century—and the issue

where business could most effectively adopt a leadership role—is climate

change.”[10]

The Climate Group website[11]

lists case studies of companies and communities that are reducing their

emissions and saving money.

In

November 2004, essentially all of the world’s industrial nations

ratified the Kyoto Protocol to reduce the emissions of GHG gasses (the

U.S. and Australia are the only significant holdouts). The Protocol

came into force February 16, 2005, launching a new “carbon-constrained” era for the 141 countries

that ratified it.[12]

Among its many provisions, the accord established regulations

limiting the amount of carbon that nations can emit, and created a

carbon market through which companies that reduce further than they are

required can sell this extra reduction to companies unable to meet their

targets.

European countries, as members of the Kyoto Protocol, are now bound by

this mandatory trading regime. The European Commission plans to cut

energy use 20% by 2020 and increase European use of renewable energy to

12% by 2012. This should reduce Europe’s emissions by a third. The

program is projected to save 60 billion Euros, create millions of new

jobs and increase European competitiveness. American businesses are at

risk of losing ground to European competitors as they innovate to meet

these goals.

For

example, STMicroelectronics (ST), a Swiss-based, $8.7 billion,

multi-national semiconductor company, set a goal of zero net GHG

emissions by 2010 while increasing production 40-fold.[13]

The main sources of ST’s GHG emissions are 45% facility energy

use, 35% industrial process (PFC[14]

and SF6[15])

emissions and 15% more efficient transportation. Its strategy is to

reduce on-site emissions by investing in co-generation (efficient

combined heat and electricity production[16])

and fuel cells (efficient electricity production).

By 2010

co-generation sources should supply 55% of ST’s electricity with another

15% coming from fuel switching to renewable energy sources. The rest of

the reductions ST is seeking will be achieved through improved energy

efficiency (hence reducing the need for energy supply) and various

projects to sequester carbon. ST’s commitment has driven corporate

innovation and improved profitability. During the 1990s, its energy

efficiency projects averaged a two-year payback (a nearly 71% after-tax

rate of return).[17]

Making

and delivering on this promise has also driven ST’s corporate innovation

and increased its market share, taking the company from the number 12

micro-chip maker to the number six in 2004.[18]

By the time ST meets its commitment, it predicts that it will have saved

almost a billion dollars.

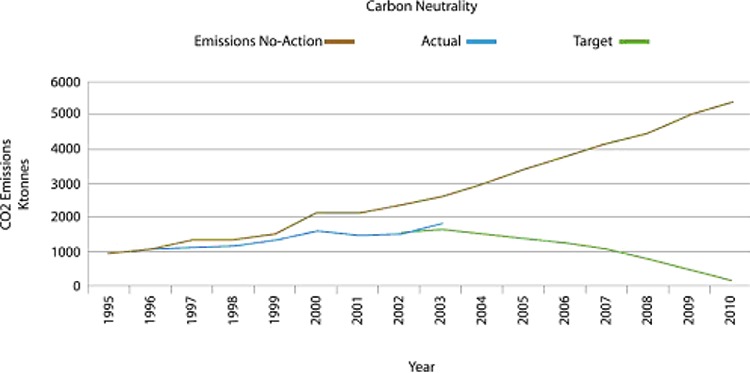

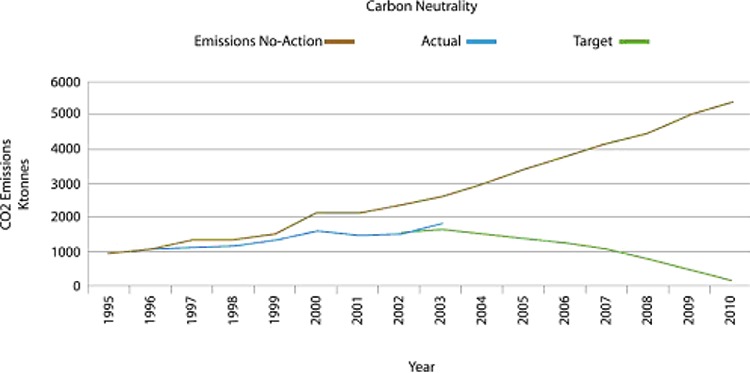

Figure: STMicroelectronics

commitment to Carbon Neutrality[19]

In

January 2005, an independent commission of businesspeople, politicians

and scientists[20]

released a report to the G8 meeting, urging member countries to

cut carbon emissions, double their research spending on green technology

and work with India and China to build on the Kyoto Protocol’s

mechanisms for carbon-saving projects. The report recommended that the

major countries agree to generate a quarter of their electricity from

renewable sources by 2025 and to shift agricultural subsidies from food

crops to biofuels.

The

report recommended wider international use of emission trading schemes,

which are already in use in the European Union, under which unused CO2

quotas are sold.

The

profit motive, stated the report, is expected to drive investment in new

technology to cut emissions further.

The

advent of the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) carbon trading mechanism

provides companies and other organizations emitting GHGs both the

opportunity to systematically reduce their emissions, sell greater

reductions in emissions and participate in a proven risk-management

system of futures contracts and financial derivatives.[21]

CCX is

North America’s only, and the world’s first, GHG emission registry,

reduction and trading system for all six GHGs of which CO2

dominates. It recently announced a partnership to create the Canadian

Climate Exchange, and is in negotiations with such countries as China

and India. It also offers offset projects in the United States, Canada,

Mexico and Brazil. It is a self-regulatory, rules-based exchange

designed and governed by its members.

Members

make a voluntary but legally binding commitment to reduce GHG

emissions. By the end of Phase I (December, 2006) all members will have

reduced direct emissions 4% below a baseline period of 1998-2001. Phase

II, which extends the CCX reduction program through 2010, will require

all new members to reduce GHG emissions 6% below baseline and extends

current members commitment to an additional 2% reduction below

baseline. In the first year, members of the exchange collectively

reduced their carbon emissions by 9%, or 2% more than would have been

required had the U.S. been a member of the Kyoto Protocol. Companies

undertaking such programs are finding that it can save significant

amounts of money.

Opening

with 16 members in December of 2004, CCX now has over 200 members

(including such businesses as DuPont, and American Electric Power, IBM,

Ford Motor Co. IBM, Motorola, Dow Corning, Waste Management and Baxter

Health Care) representing over 8% of all direct U.S. GHG emissions. The

State of New Mexico, cities such as Chicago and Boulder, universities

such as Presidio School of Management, Tufts and University of Oklahoma, and

a wide array of smaller businesses and non-profit groups are also

members.[22]

CCX has

proven that businesses can engage in reduction of emissions and remain

profitable. But it is only the first of a growing number of efforts to

create carbon markets in the United States. The seven Northeastern

states have approved the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a mandatory

regulatory scheme. Over 20 states have already either passed or

proposed legislation on CO2

emissions, or have developed carbon registries.

In

August 2006, California became the first state in the nation to impose

mandatory limits on GHG emissions, requiring a 25% cut in GHGs by 2020

that would affect companies from automakers to manufacturers. The state

is the 12th largest carbon emitter in the world despite

leading the nation in energy efficiency standards and its lead role in

protecting its environment.[23]

The California Chamber of Commerce opposed the bill, but such business

groups as A New Voice for Business[24]

supported the measure, stating that it would create jobs and help to

launch a whole new industry in California.

Many believe the legislation will be the turning point in the country's

global warming policy.

There

is now such a proliferation of inconsistent carbon reduction regimes

that in April 2006, a group of major businesses called on Congress to

pass national legislation capping carbon emissions to relieve them of

having to navigate the competing schemes.

At the

hearing before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee leaders

representing eight big energy companies, including GE, Shell and the two

largest owners of utilities in the United States,

Exelon and Duke Energy, spoke. Six of the eight said they would welcome

or accept mandatory caps on their GHG emissions. Wal-Mart executives

also spoke in favor of carbon caps. The companies stated that federal

regulations would bring stability and sureness to the market. David

Slump, the top marketing executive in GE’s energy division, stated, “GE

supports congressional action now.” Two representatives from the energy

sector, Southern Company and American Electric Power, called for a

voluntary rather than mandatory program, but they acknowledged that

regulations may be coming, and offered detailed advice on how they

should be designed.

[25]

At

subsequent Senate hearings on global warming, Senator Bingaman asked

representatives of CCX whether there were any reasons that the U.S.

should not simply implement CCX as the basis for a regulated U.S. carbon

market. Cities, counties and companies that join CCX might, thus, just

be ahead of the regulatory game.

While

it is highly likely that some form of national cap and trade system will

emerge in the U.S. soon,

companies should not wait until they are forced to limit their

emissions. The early adopters gain substantial first mover advantages.

As

energy prices have risen, many companies have chosen to go ahead and

implement energy savings measures. Over a 12-year period in the 1980s,

Dow’s Louisiana plant was able to save enough energy implementing worker

suggested savings measures to add $110 million each year to the bottom

line. Each measure also reduced Dow’s carbon footprint.[26]

In

2000, as part of re-branding itself as “Beyond Petroleum,” British

Petroleum (BP) announced a corporate commitment to reduce its emissions

of GHGs. In 1997, in a speech at Stanford University, California, group

chief executive Lord Browne stated, “BP accepted that the problem was

potentially very serious and that precautionary action was justified.”

BP then announced a target for 2010: that GHG emissions from its own

operations would be 10% lower than emissions in 1990. BP achieved that

target at the end of 2001, nine years ahead of schedule, and gained

around $750 million in net present value through increased operational

efficiency, the application of technological innovation and improved

energy management. While returns on traditional investments average

40-50%, investments in increasing energy efficiency often return 70% or

more.[27]

BP is now one of the world’s largest solar companies and

sees its 50-year future as one of transition away from fossil fuels to

becoming an energy company.

Financial savings are not the only reason that companies engage in such

behavior. Rodney Chase, a senior executive at BP, subsequently

reflected that even if the program had cost BP money, it would have been

worth doing because it made them the kind of company that the best

talent wants to work for.[28]

It is reducing costs, gaining market share and attracting

and retaining the best talent.[29]

DuPont,

an even earlier entrant into the field, committed itself to reducing its

GHGs by 65% from 1990 to 2010. The company also set plans to raise

revenues 6% per year from 2000-2010 with no increase in energy use; and

by 2010, source 10% of its energy and 25% of its feed-stocks from

renewable sources. The company announced these goals in the name of

increasing “shareholder and societal value.”

To

date, DuPont has kept energy use the same and increased production by

30%. Globally, DuPont’s emissions of GHGs are down 72%. Global energy

use is 7% below 1990 levels, and the company is on track with its

renewable energy targets. It estimates that this program has already

saved the company $3 billion.[30]

In one example, four engineers at DuPont recently figured out how to

spend less than $100,000 to save nearly $7 million per year in energy

costs.[31]

Under

CEO Mike Eskew, United Parcel Service (UPS) has assembled one of the

biggest alternative-fuel fleets, around 1,500 vehicles strong. In

February 2006, UPS announced that it had placed an order for 50

new-generation hybrid-electric delivery trucks, which will reduce fuel

consumption by 44,000 gallons over the course of a year.[32]

Many

participants in the voluntary U.S. EPA performance-challenge programs

(such as 33/50[33]

and Green Lights[34])

reported that energy efficiency enabled them to capture multiple

benefits. For example, Sony Electronics’ U.S. and Mexican facilities

voluntarily installed energy efficient lighting where it was

cost-effective and did not interfere with the quality of light. By the

end of 1994, the organization had upgraded approximately 6.1 million

square feet of floor space with new lighting fixtures, reduced its

operating expenses by more than $915,000 per year and lowered energy

demand by almost 12 million kilowatt hours annually. In addition, these

lighting changes indirectly prevented more than 7,300 tons of air

pollution from being emitted by local utility companies.[35]

Sony

found its participation in the EPA’s Green Lights program often improved

visual performance so significantly that it led to significant increases

in labor productivity and reductions in error rates. The financial

benefits from this far outweigh the value of the energy savings. For

example, Boeing implemented a lighting system retrofit in its design and

manufacturing areas. The program cut lighting energy costs by 90% with

a less than 2-year payback, but because workers could see better they

avoided rework—the error rate decreased 30%—which increased on-time

delivery, and enhanced customer satisfaction.[36]

Lockheed commissioned a new headquarters building for its Sunnyvale

facility. The architects successfully argued that the “literium” that

provided day-lighting throughout the structure was not merely a worker

amenity, but was essential to the performance of the building. They

were right: the lighting system resulted in a 75% reduction in lighting

energy usage. This contributed to enabling the building to use half the

energy of a comparable standard building. The different design added $2

million to the cost of the building—the reason the “value engineers”

sought to eliminate it from the design. However, it is saving Lockheed

$500,000+ per year worth of energy, or a four-year payback. The

greatest benefit to Lockheed was the effect on their human capital:

because workers enjoyed the space, absenteeism dropped by 15% and

productivity increased 15%. The gains from this won Lockheed a very

competitive contract, the profits from which paid-off the entire costs

of the building.[37]

It

appears that people simply perform better in well-designed spaces. A

study by Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) showed that in good

“green” buildings, day-lighting can enable students to achieve 20 to 26%

higher test scores, and retail stores to have up to 40% higher sales

than conventional stores.[38]

In

1987, the former NMB Bank in The Netherlands completed a new 538,000

square foot headquarters. The bank’s management, desiring to improve

the somewhat stodgy image of the company, commissioned the creation of a

“green headquarters.” The building uses 10% of the energy of a similar

building constructed at the same time (90% savings). The annual energy

savings of $2.9 million required only $700,000 additional building

cost—a three-month payback on energy costs alone. Employees reported

being more comfortable and absenteeism declined 15%, dramatically

increasing project return on investment. The new headquarters achieved

its goal: it dramatically improved the image of the bank—which became

the second largest bank in the Netherlands.

The bank renamed itself and subsequently bought Bearings.[39]

Community programs to reduce energy use are particularly good for small

businesses. Back in the 1970s when energy prices were rising,

communities began implementing programs to reduce their use of energy.

The results were extraordinary, and can be replicated today.

In 1974, the Osage Municipal Utility was faced with the need

to build a new power plant to meet growing demand. Its general manager,

Wes Birdsall, realized that if he built the plant, it would increase

everyone’s rates. Instead, he stepped across the meter to his

customers’ side and helped them use less of his product: electricity.

Why on earth would a businessman ever do that?

Birdsall realized that what his customers wanted was not raw

kilowatt-hours, but the energy “services” of comfort in their homes:

shaft-power in factories, illumination, cold beer and the other services

that energy delivers. People buy energy, but what they really want is

the service. If they can get the same or improved service more cheaply

using energy more efficiently or from a different source, they will jump

at it. Birdsall realized that if he raised his prices, not only would

he be doing his customers a disservice, but that they might turn to

other options. By meeting their desires for energy services at lower

cost, he retained them as customers, and began one of the most

remarkable economic development stories in rural America.

Birdsall’s program was able to save over a million dollars a

year in this town of 3,800 people and generate over 100 new jobs. A

report on the program found that, “Industries are expanding and choosing

to remain in Osage because they can make money through employees who are

highly productive and through utility rates that are considerably lower

than neighboring cities.”[40]

Birdsall was able to reduce electric bills to half that of the state

average and unemployment to half that of the national average, because

with the lower rates new factories came to town. He held electric

growth level until 1984. The program was profiled in the Wall Street

Journal, and was copied by other utilities.

According to a USDA study of Osage, “The local business

people calculated that every $1 spent on ordinary consumer goods in

local stores generated $1.90 of economic activity in the town’s

economy. By comparison, petroleum products generated a multiplier of

$1.51; utility services, $1.66; and energy efficiency, $2.23. Moreover,

the town was able to attract desirable industries because of the reduced

energy operating costs resulting from efficiency measures put in place.

Energy efficiency has a long and successful track record in Osage as a

key economic development strategy.”[41]

Thirty

years later, a June 2006 article in Business Week pointed out that small

businesses, the economic engine of growth, will be especially hard hit

by climate change, and can disproportionately benefit from programs to

reduce their emissions, stating:

It’s increasingly likely that a mandatory program to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions will come to pass. This prospect of further

government regulation is one reason small business owners should pay

attention.

But it’s not the only one. Small firms could well be among the hardest

hit victims of climate change.

Extreme weather events, for example, can wipe out an entire

region’s small businesses in one fell swoop. And they can't readily

bounce back from disruptions caused by natural disasters. Look at the

impact of Hurricane Katrina on small businesses in the Gulf Coast region, where

they constituted the backbone of the economy . . .

There’s been virtually no research on what global warming means for

small business, even though 23 million U.S. small businesses

constitute one-half of the economy.

There is some good news for small businesses, however. To start

with, reducing energy waste in U.S. homes, shops, offices,

and other buildings must, of necessity, rely on tens of thousands of

small concerns that design, make, sell, install and service

energy-efficient appliances, lighting products, heating,

air-conditioning and other equipment.

What’s more, devising technological fixes to curb GHG emissions

must rely on the capacity of small business innovators and entrepreneurs

to produce “clean-tech” breakthroughs in photovoltaics, distributed

energy, fiber-optic sensors, and the like.

Finally, every single small business in the nation can profit by

making its own workplace more energy-efficient. According to the EPA’s

Energy Star Small Business program, small firms can save (at least) 20%

to 30% on their energy bills through off-the-shelf cost-effective

efficiency upgrades. The job consists largely of installing the same

few simple devices—programmable thermostats, for example—over and over

again in millions of small business workplaces.[42]

Small

office buildings can achieve similar savings. A project to remodel a

2,800 square foot law office in Louisiana improved employee productivity

with energy systems that saved over $6,000 while eliminating 50 tons of

CO2

emissions per year.[43]

In

1989, the municipal utility in Sacramento, California

shut down its 1,000-megawatt nuclear plant. Rather than invest in any

conventional centralized fossil fuel plant, the utility met its

citizens’ needs through energy efficiency and such renewable supply

technologies as wind, solar, biofuels and distributed technologies like

co-generation, fuel cells, etc. In 2000, an econometric study showed

that the program has increased the regional economic health by over $180

million, compared to just running the existing nuclear plant. The

utility was able to hold rate levels for a decade, retaining 2,000 jobs

in factories that would have been lost under the 80% increase in rates

that just operating the power plant would have caused. The program

generated 880 new jobs, and enabled the utility to pay off all of its

debt.

Toyota’s Torrance, California office complex, completed in 2003,

combines energy-efficiency strategies such as roof color, photovoltaic

solar electricity and “little things,” including an advanced building

automation system, a utilities metering system, natural-gas-fired

absorption chillers for the HVAC system, an Energy Star cool roof system

and thermally insulated, double-paned glazing. The 600,000+ square foot

campus exceeds California’s stringent energy efficiency requirements by

24% at no additional cost than a conventional office building.[44]

A

recent article by utility regulator S. David Freeman, once Chair of the

Tennessee Valley Authority, and Jim Harding of the Washington State

Energy Office announced that a company called Nanosolar is building a

$100 million manufacturing facility in California to produce solar cells

very cheaply. The resulting solar panels would bring the cost of power

to below what is now available in a large part of the world.

Backed by a powerful team of private investors, including Google’s

two founders and the insurance giant Swiss Re, Nanosolar announced plans

to produce 215 megawatts of solar energy next year, and soon thereafter

capable of producing 430 megawatts of cells annually.

What makes this particular news stand out? Cost, scale and

financial strength. The cost of the facility is about one-tenth that of

recently completed silicon cell facilities.

Second, Nanosolar is scaling up rapidly from pilot production to

430 megawatts, using a technology it equates to printing newspapers.

That implies both technical success and development of a highly

automated production process that captures important economies of

scale. No one builds that sort of industrial production facility in the

Bay Area—with expensive labor, real estate and electricity costs—without

confidence.

Thin solar films can be used in building materials, including

roofing materials and glass, and built into mortgages, reducing their

cost even further. Inexpensive solar electric cells are, fundamentally,

a “disruptive technology,” even in Seattle, with below-average

electric rates and many cloudy days. Much like cellular phones have

changed the way people communicate, cheap solar cells change the way we

produce and distribute electric energy. The race is on.

The announcements are good news for consumers worried about high

energy prices and dependence on the Middle East, utility executives worried about the long-term viability of

their next investment in central station power plants, transmission, or

distribution, and for all of us who worry about climate change. It is

also good news for the developing world, where electricity generally is

more expensive, mostly because electrification requires long-distance

transmission and serves small or irregular loads. Inexpensive solar

cells are an ideal solution – by far the least expense way to bring

electric power to areas not now served by an electric grid, safer from

terrorists and saboteurs, and able to be put “on-line” years ahead of

traditional central generation plans and their elaborate transmission

and distribution systems.

Meanwhile, the prospect of this technology creates a conundrum for

the electric utility industry and Wall Street. Can—or should—any

utility, or investor, count on the long-term viability of a coal,

nuclear or gas investment? The answer is no. In about a year, we’ll

see how well those technologies work. The question is whether federal

energy policy can change fast enough to join what appears to be a

revolution.[45]

Renewable options are not only the best choice for developing countries;

they are now the fastest growing form of energy supply around the world,

and in many cases are cheaper than conventional supply. Solar thermal

is outpacing all conventional energy supply technology around the

world. Modern wind machines come second, delivering almost 8,000

megawatts of new capacity a year, or more than nuclear power did at the

peak of its popularity. The next fastest growing energy supply

technology is solar electric, even at current prices.[46]

Renewables can also be cheaper than any conventional supply. Energy

from wind turbines in good sites now costs 3¢ per kilowatt-hour (kWh).[47]

And once the turbine is constructed, the fuel is free forever more.

Just running an existing coal plant costs 5¢ to 6¢ per kWh. Solar

electric is more expensive, although about a dozen companies are

competing to deliver amorphous thin-film solar at 3¢ per kWh. Such

renewable technologies lend themselves to construction and delivery by

small to medium sized enterprises - the backbone of most economies

around the world.

The

Governor of Pennsylvania recently announced the opening of a factory to

make wind machines. Creating 1,000 new jobs over the next five years,

it is the biggest economic development measure for Johnstown, PA, in

recent memory. The city of Chicago underwrote Spire solar to enable the

company to open a manufacturing plant in Chicago. The city wanted the

jobs and to be able to install solar on municipal buildings. California

has announced that it will spend over $8 million installing solar in

2006, and create a $1.5 billion investment fund to help environmentally

responsible companies that are developing cutting-edge clean energy

technologies.

A 2006

study by University of California professors recently found that

investments in renewable energy create ten times as many jobs as

investments in fossil supply.[48]

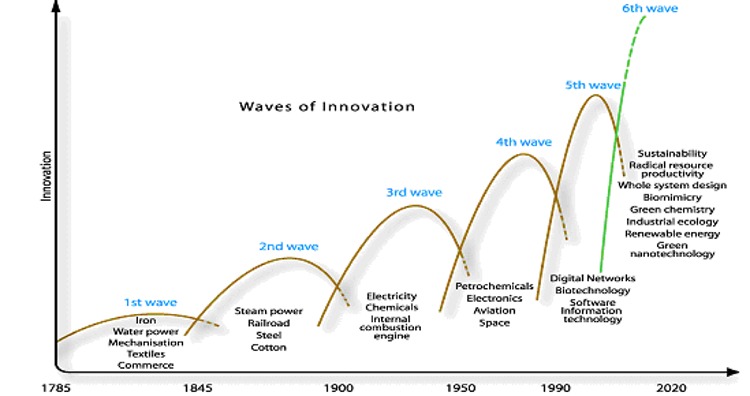

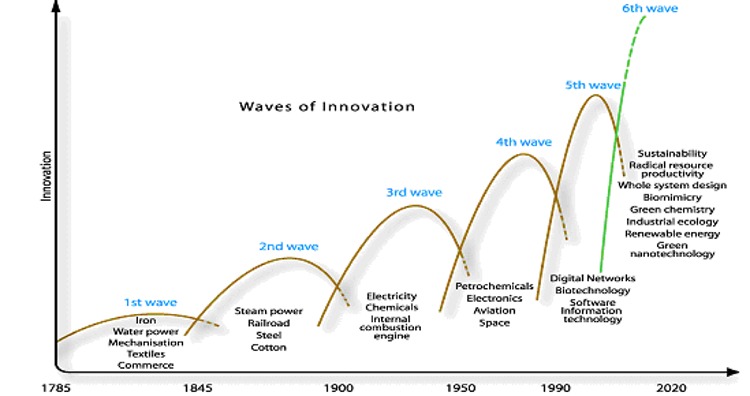

Business success in a time of technological transformation demands

innovation. Since the Industrial Revolution, there have been at least

six waves of innovation, which shifted the technologies that underpinned

economic prosperity. In the late 1700s textiles, iron mongering,

water-power and mechanization enabled modern commerce to develop.

The

second wave saw the introduction of steam power, trains and steel. In

the 1900s, electricity, chemicals and cars began to dominate. By the

middle of the century it was petrochemicals, and the space race, along

with electronics. The most recent wave of innovation has been the

introduction of computers, also known as the digital or information

age. As the industrial revolution plays out and economies move beyond

iPods, older industries will suffer dislocations, unless they join the

increasing number of companies implementing the array of sustainable

technologies that will make up the next wave of innovation.

Figure: Waves of Innovation[49]

Aidan

Murphy, vice president at Shell International, stated in 2000: "The Kyoto treaty has prompted us to shift some of its [Shell’s] focus

away from petroleum toward alternative fuel sources. While the move has

helped the company make early strides toward its goal of surpassing

treaty requirements and reducing emissions to 10% less than 1990 levels,

Shell is being driven largely by the lure of future profits… We

are now involved in major energy projects involving wind and biomass,

but I can assure you this has nothing to do with altruism… We see

this as a whole new field in which to develop a thriving business

for many years to come. Capital is not the problem, it’s the lack of

ideas and imagination.[50]

Sweeden

has set a national goal of an oil-free economy by 2020 without building

any new nuclear plants. A report in the BBC stated, “The country aims

to replace all fossil fuels with renewables before climate change

damages economies and growing oil scarcity leads to price rises.” The

program is driven in part by worry on the part of The Royal Swedish

Academy of Sciences that oil supplies are peaking, and that high oil

prices could cause global economic recession. In 2003, 26% of all

energy consumed came from renewables.[51]

To

drive such innovation, Sweden,

along with Germany and other European nations are experimenting with

what is called “Tax Shifting.” This would increase the taxes on

resource use, while lowering employment taxes and other disincentives to

use more people. Lester Brown recently reported that, "A four-year plan adopted in Germany in 1999

systematically shifted taxes from labor to energy. By 2001, this plan

had lowered fuel use by 5%. It had also accelerated growth in the

renewable energy sector, creating some 45,400 jobs by 2003 in the wind

industry alone, a number that is projected to rise to 103,000 by 2010."

Both

Japan and China are now considering implementing such tax shifts.[52]

Recently, 2,500 economists, including eight Nobel Prize laureates in

economics, endorsed the concept of tax shifts. Harvard economics

professor N. Gregory Mankiw wrote in Fortune: "Cutting income taxes while increasing gasoline taxes would lead to

more rapid economic growth, less traffic congestion, safer roads and

reduced risk of global warming—all without jeopardizing long-term fiscal

solvency. This may be the closest thing to a free lunch that economics

has to offer."[53]

Without such a shift in policies, jobless growth for major corporations

worldwide is likely to remain not a forecast, but an established trend.

The world’s 500 largest corporations have managed to increase their

production and sales by 700% over the past 20 years, while at the same

time reducing their total workforce. The outsourcing of

industrial jobs to China and service jobs to India has accelerated the

impact of this process.[54]

At the same time however, good people

are increasingly critical for the functioning of any business that seeks

to compete in the Knowledge Economy. Tom Peters, one of the world’s

leading business authors, states: "We

are in the midst of redefining our basic ideas about what enterprise and

organization and even being human are–about how value is created and how

careers are pursued. Welcome to a world where “value” (damn near all

value!) is based on intangibles—not lumpy objects, but weightless

figments of the Economic Imagination. We have entered an Age of

Talent. People (their creativity, their intellectual capital, their

entrepreneurial drive) is all there is. Enterprises that master the

market for talent will do better than ever. But to attract and retain

the Awesome Talent, an organization must offer up an Awesome Place to

Work."[55]

As

stated above, this is driving such companies as BP to make public

commitments to cut their emissions as a strategy for attracting and

retaining the best talent.

Richard

Florida, in his book, The Rise of the Creative Class,[56]

points out that the cutting-edge businesses follow the knowledge

workers, establishing corporate operations where they can access this

new class of talent. He notes that regions that wish to be economically

successful will do what it takes to attract the knowledge workers, which

includes preserving the environment and establishing the sort of

innovative cultural atmosphere that such people treasure.

The

failure by the American federal government to take action on global

warming has created a leadership vacuum that is rapidly being filled by

cities, states and businesses.

In the

U.S., over 355 cities have formally committed to take following three

actions:

-

Strive to meet or beat the Kyoto

Protocol targets in their own communities, through actions ranging

from anti-sprawl land-use policies to urban forest restoration

projects to public information campaigns;

-

Urge their state governments, and

the federal government to enact policies and programs to meet or

beat the GHG emission reduction target suggested for the United

States in the Kyoto Protocol—7% reduction from 1990 levels by 2012;

and

-

Urge the U.S. Congress to pass the

bipartisan GHG reduction legislation, which would establish a

national emission trading system[57]

The

International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives’ (ICLEI)

“Cities for Climate Protection Program”[58]

offers a coherent program a community can follow to implement a global

warming mitigation program. This manual is offered as part of that

program.

These

cities now understand a simple but important formula: climate

protection saves tax dollars. In fact, climate protection can protect a

city and its taxpayers from one of the most volatile demands that

municipal budgets are likely to face in the years ahead: fossil energy

prices.

In

longhand, the formula goes like this: Global warming is slowed by

reducing GHG emissions. GHG emissions are cut by reducing the

consumption of fossil fuels. Fossil fuel use is cut by employing energy

efficiency measures. Energy efficiency measures lead to lower energy

bills. Lower energy bills mean lower operating costs. Lower costs for

city operations save citizens tax dollars. So, taking action to slow

global warming is one way to reduce tax expenditures. The savings can

be used to cut taxes, to slow their growth, to improve critical city

services that have been under-funded in the past, or to invest in more

energy efficiency improvements (see case study).

|

|

|

CASE STUDY: States of Michigan and Oregon

|

In Ann Arbor,

Michigan, a Municipal Energy Fund was established in 1998 to be

a self-sustaining source of funds for investment in

energy-efficient retrofits at city facilities, so the city would

be able to continually reduce its operating costs over time.

The city operates 60 facilities and spends $4.5 million per year

on energy (out of an annual budget of $288 million in 2005).

The Fund is administered by the city’s Energy Office under the

supervision of a three-person board, which must approve all

projects. The Fund has invested in street light improvements,

parking garage lighting, a boiler, two electric vehicles and

photovoltaic cells. By providing the difficult up-front costs

and then capturing 80% of the resulting savings, the Fund

motivates facility managers to undertake energy efficient

projects, and became self-sustaining in 3-5 years requiring no

additional annual appropriations.

To launch its energy

efficiency program, in late 1990s, Portland, Oregon created a

“One Percent for Energy” program. It assessed eight municipal

bureaus 1% of their energy bill to raise $70,000 a year for

efficiency improvements without requiring direct support from

the city’s general fund. In return, contributing bureaus were

given technical assistance to help them save money through

energy efficiency improvements. The 1% is based on previous

years energy bills including transportation, fuels, electricity,

etc with a max of $15,000 per bureau. To date, the program

successfully brings in approximately $70,000 each year.

CONTACT

Portland’s Office of Sustainable Development Energy Efficiency and

Renewable Energy

(503) 823-7582

|

Energy

costs—and potential savings—are likely to increase in the future. Many

experts predict that the volatility in fossil energy supplies and prices

will continue. Most scientists now agree natural gas and oil are finite

resources and that world oil production is expected to peak in the next

couple of decades. China, India and other rapidly developing countries

are competing with the U.S. for the same supplies, pushing up prices.

Severe storms like Hurricane Katrina, which experts predict will become

more common with global warming, can cause petroleum supply

disruptions. Conflicts in, or political disputes with, oil-producing

countries also will cause disruptions to oil and gas supplies. Even

coal, which the U.S. currently mines in abundance, may prove to be a

more expensive way to produce electricity in the future, as the industry

invests in new processing technologies and sequestration measures to

reduce carbon emissions.

During

the winter of 2005-2006, the Massachusetts Municipal Association asked

city managers around the state whether they expected increased energy

costs. Sixty-five percent said they believed that energy costs would

increase by more than 10% in the coming year—and one in four expected

costs to increase by more than 25%.

In

1991, well before global warming because a prominent issue for the

public, Portland launched a “City Energy Challenge” to cut the annual

energy bill of city buildings by 10% over 5 years. Over the last 15

years, the city saved $15 million and generated an additional $1.2

million in incentive payments from state government and utilities.

In

addition, the city negotiated a purchase of wind energy from Portland

General Electric, further reducing its demand for coal-fired

electricity, preventing 4,500 metric tons of CO2

emissions over five years, and deriving part of the city’s energy

from a resource that is immune from volatile price spikes because wind

is a “free” fuel.

The

city of New Haven, Connecticut, another leader in picking the

low-hanging fruit of energy efficiency, created an energy conservation

program in 1994 and estimates it has saved $24.7 million since then by

doing simple measures.

Local

schools provide a dramatic example of the savings waiting to be captured

by public institutions. Schools in the U.S. reportedly spend more than

$6 billion each year on energy, more than they spend on computers and

books combined. In the typical school, about a third of that energy is

wasted. Cost-effective energy efficiency measures could easily save 25

to 30% of school energy bills, enough to hire 30,000 new teachers[59]

while reducing the schools’ contributions to global warming. Yet, some

of the most obvious ways to save energy remain undone. An example: In

the fall of 2005, two energy consultants in New Haven, CT, found a way

to save the local school district $1.1 million in one year—by the

elementary act of turning down thermostats when school buildings were

not in use.[60]

These

stories—and similar examples in cities across the U.S.—illustrate the

multiple benefits of a municipal climate protection program. In this

time of global warming and energy volatility, energy efficiency,

renewable energy technologies and climate protection are three pillars

of sound fiscal stewardship.

By

investing in energy efficiency and renewable energy systems, local

communities are also preparing themselves for the possibility of

heightened regulations regarding GHGs coming in the future. Cities and

companies that adopt the Kyoto Protocol agreements, and reduce GHG

emissions below 1990 levels, will be able to sell their emission credits

in any one of several carbon emission exchanges and stand a better

chance of avoiding down-graded bond or stock ratings.

|

|

CASE STUDY: U.S. Army

|

|

Energy efficiency

and renewable energy are of particular interest to the U.S.

military. It has not been lost on those tasked with the

security of the country that wasted energy, and dependence of

foreign sources compromises their mission. A growing number of

bases and commanders are implementing programs to reduce waste

and secure greater energy supplies from local sources.

At Fort Detrick,

Maryland, an energy performance contract will save 33,000 tons

of CO2 and $2.9

million annually.[61]

Fort Carson's goal is 100% renewable energy by 2027; it is a 25

year plan initiated in 2002.

Fort Carson also

has interim goals to achieve 40% of electricity and 10% of

facility heat from renewable sources by 2013.[62]

CONTACT

Christopher Juniper

|

The

bottom line is simple: Protecting the climate is good fiscal

stewardship. Global warming is an issue with many dimensions. For many

people, the most important issue is the pocketbook—and the pocketbook is

a strong argument for municipal climate action, sooner rather than

later.

In a

world that overwhelmingly recognizes climate change as a serious threat,

businesses within a community that ignore it are increasingly seen as

irresponsible. Conversely, an aggressive business posture to reduce GHG

emissions is becoming a proxy for competent corporate governance. A

2003 Columbia Journal of Environmental Law article demonstrated the

legal feasibility of lawsuits holding companies accountable for climate

change. Though the effects of such litigation on companies’ market

value and shareowner value remains to be seen, the first such suits have

already been filed.[63]

In the

U.S., the Sarbanes-Oxley Act[64]

makes it a criminal offense for the Board of Directors of a company to

fail to disclose to shareholders information that might materially

affect the value of the stock. This includes environmental liabilities

(including GHG emissions) that could alter a reasonable investor’s view

of the organization. In France, The Netherlands, Germany[65]

and Norway, companies are already legally required to publicly report

their GHG emissions.

A

group of 143 institutional investors writes annually to the

Financial Times

500, the largest quoted companies in the world by market capitalization,

asking for disclosure of investment-relevant information concerning

their GHG emissions.[66]

Initially, perhaps 10% of the recipients bothered to answer the survey.

In 2005, 60% answered. Companies like Ford Motor Company produced a

major report detailing its emissions. Why the change? Passage that

year of Sarbanes Oxley clearly played a role. Perhaps more

significantly, the Carbon Disclosure Project represents institutional

investors with assets of over $31.5 trillion. Increasingly, companies

that wish to limit their risk exposure, obtain insurance or get

financing are implementing programs to reduce their emissions of GHGs.

The

FTSE Index, the British equivalent of Dow Jones, states: "The impact of climate change is likely to have an increasing

influence on the economic value of companies, both directly, and through

new regulatory frameworks. Investors, governments and society in

general expect companies to identify and reduce their climate change

risks and impacts, and also to identify and develop related business

opportunities."[67]

The banking industry is also reducing its greenhouse footprint. In

2006, HSBC won the Financial Times’ First Sustainable Banking Awards for

being the first bank to become carbon neutral. It has purchased

renewable energy for itself, and provided financing for renewable energy

companies.[68]

Wall

Street’s most prestigious investment bank, Goldman Sachs, is putting $1

billion into clean-energy investments. It has also pledged to purchase

more products locally.[69]

In

March 2006, the business and investment network CERES released a report

showing that many major American companies were more potentially liable

for lawsuits and other risks than their European counterparts because of

their emissions of climate changing gasses. The New York Times stated,

Dozens of U.S.

businesses in various climate-vulnerable sectors ... are still largely

dismissing the issue or failing to articulate clear strategies to meet

the challenge. Companies that disclose the amount of emissions of

heat-trapping gases they produce and take steps to limit them cut their

risks, including potential lawsuits from investors.[70]

A

growing number of investors are concerned about climate change. The

number of investors participating in the Investor Network on Climate

Risk (INCR, the leading group on sustainable investing) has quadrupled

in the past three years, and the collective assets of INCR members

increased from $600 billion to $2.7 trillion (an increase of 450%).[71]

While cities are not directly involved, it is important to understand

the trends occurring in the financial sector.

Large institutional investors are leading the way. Institutional

investors have reason to be concerned about the impact of climate risk

on their portfolios, and have been successful in urging companies to

increase disclosure of climate risk by engaging the companies with an

enduring shareholder campaign. Despite these successes, some investors

are still frustrated with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which

has done little to mandate disclosure of climate risk, and with many

companies that have not yet taken proactive steps to address climate

risk.

A

group of 28 leading institutional investors from the U.S. and Europe,

who manage over $3 trillion in assets, announced a ten-point action plan

which calls on investors, leading financial institutions, businesses,

and government to address climate risk and seize investment

opportunities.[72]

The plan represents the first time that American and European investors

have cooperated on a comprehensive climate risk initiative.

The 2005 action

plan calls on U.S. companies, Wall Street firms and the Securities and

Exchange Commission to intensify efforts to provide investors with

comprehensive analysis and disclosure about the financial risks

presented by climate change. The group also pledged to invest $1

billion in prudent business opportunities emerging from the drive to

reduce GHG emissions.

Climate change will have an impact on the value of investments, and

could cost U.S. public companies billions of dollars, ranging from

unexpected drops in earnings due to fines and clean-up costs (following

the violation of environmental laws), increased operating costs

(following changes in environmental regulations), and greater than

expected management costs due to understated or undisclosed liabilities.

Investors are starting to evaluate

corporations on the basis of their preparedness for associated risks and

opportunities. Indeed, some investors believe that companies that can’t

adapt to a carbon-constrained world will be forced to compete with

forward-thinking competitors ready to leverage new business models and

capitalize on emerging markets in renewable energy and clean

technologies.

Despite the likely threat of global

warming, the largest CO2

polluters in the U.S. are failing to address the related financial

risks. A recently released study by the nonprofit Investor Responsibility Research Center

(IRRC) finds that while foreign rivals struggle to meet European Union

CO2

emission reduction targets, American companies such as ChevronTexaco,

ExxonMobil, General Electric and Xcel Energy continue to ignore the

threat of global warming.[73]

While it is not a current threat, cities

may find their own bond ratings down-graded if they fail to take steps

to prepare their own buildings and the homes and buildings of their

residents and businesses to meet the climate challenge.

Other investors are using the power of

shareholder resolutions, which mandate yes or no votes on specific

practices at corporate annual meetings to affect company policies on

climate change. According to the nonprofit Investor Network on Climate

Risk, 28 shareholder resolutions calling for companies to either

quantify and reduce GHG emissions or disclose corporate responses to

climate change risks and opportunities were filed at 22 companies in

2004.[74]

While the majority of such resolutions fail, the pressure often makes an

impact, sending executives scurrying to make changes in anticipation of

growing investor concern.

Companies which received resolutions included Allergan, Anadarko

Petroleum, Analog Devices, Apache, Avery Dennison, Centex, Chevron,

Corning, Dominion Resources, Dow Chemical, ExxonMobil, FirstEnergy, Ford

Motor Company, General Motors, Health Care Property, JPMorgan Chase,

Lennar, Liberty Property Trust, Newell Rubbermaid, Progress Energy,

Ryland Group, Simon Property Group, Tesoro, Unocal, Vintage Petroleum,

Wachovia, Wells Fargo and XTO Energy.[75]

In

July 2004, eight state attorney generals and New York City led the

first-ever climate change lawsuit against five of the nation’s largest

electric power generating companies to require them to reduce their CO2

emissions.

In

2005, investor intervention and persuasion contributed to the decisions

by several large companies (Anadarko Petroleum, Apache, Chevron,

Cinergy, DTE Energy, Duke, First Energy, Ford Motor, GE, JPMorgan Chase

and Progress Energy) to make new commitments such as supporting

mandatory limits on GHGs, voluntarily reducing their emissions, or

disclosing climate risk information to investors.[76]

The

United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), working with the

organization Ceres, announced a new Climate Risk Disclosure Initiative

to create a global standard for climate risk disclosure.[77]

The UNEP is developing Principles for Responsible Investment to align

the long-term goals of sustainable development with the obligations of

institutional investors. Ceres and UNEP are establishing a new

international forum for collaboration and information sharing by

institutional investors on climate risk.

In

another ominous sign for chief executives and board members, some

experts in corporate governance say company officers could be held

accountable for failing to protect their companies from climate-related

risk. And the lawsuits could come from governments as well as investors

and other aggrieved parties. Peter Lehner, chief of the New York

attorney general’s Environmental Protection Bureau, said the bureau was

studying the issue of climate change and might sue polluters along the

lines of the successful tobacco litigation by states in the 1990’s.[78]

Perhaps

the greatest pressure for change, however, will come from the insurance

industry. As described above, the insurance companies are already being

battered by losses from the increase in the violence of storms. In

2003, The Wall Street Journal reported that,

With all the talk of potential shareholder lawsuits against

industrial emitters of greenhouse gases, the second largest re-insurance

firm, Swiss Re has announced that it is considering denying coverage,

starting with directors and officers liability policies, to companies it

decides aren’t doing enough to reduce their output of greenhouse gases.[79]

In

March 2004, Reuters reported: “The world’s second largest re-insurer,

Swiss Re, warned … that the costs of natural disasters, aggravated by

global warming, are spiraling out of control, forcing the human race

into a catastrophe of its own making.”[80]

In the

Fortune Magazine article “Cloudy with a Chance of Chaos,”[81]

author Eugene Linden reported, "Already the pain of weather-related insurance risks is being felt by

owners of highly vulnerable properties such as offshore oil platforms,

for which some rates have risen 400% in one year. That may be an omen

for many businesses. Three years ago John Dutton, dean emeritus of Penn

State's College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, estimated that $2.7

trillion of the $10-trillion-a-year U.S. economy is susceptible to

weather-related loss of revenue, implying that an enormous number of

companies have off-balance-sheet risks related to weather—even without

the cataclysms a flickering climate might bring."

In 2004, Swiss Re, a $29 billion

financial giant, sent a questionnaire to companies that had purchased

its directors-and-officers coverage, inquiring about their corporate

strategies for dealing with climate change regulations. D&O insurance,

as it is called, insulates executives and board members from the costs

of lawsuits resulting from their companies' actions; Swiss Re is a major

player in D&O reinsurance.

What Swiss Re is after, says Christopher

Walker, who heads its Greenhouse Gas Risk Solutions unit, is reassurance

that customers will not make themselves vulnerable to

global-warming-related lawsuits. He cites Exxon Mobil as an example:

The oil giant, which accounts for roughly 1% of global carbon emissions,

has lobbied aggressively against efforts to reduce GHGs. If Swiss Re

judges that a company is exposing itself to lawsuits, says Walker, "We

might then go to them and say, 'Since you don't think climate change is

a problem, and you're betting your stockholders' assets on that, we're

sure you won't mind if we exclude climate-related lawsuits and penalties

from your D&O insurance.'" Swiss Re's customers may be put to the test

soon in California, where Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger is pushing to

restrict carbon emissions, says Walker. A customer that ignores the

likelihood of such laws and, for instance, builds a coal-fired power

plant that soon proves a terrible bet could face shareholder suits that

Swiss Re might not want to insure against.

Alarmed

at the sharply rising cost of hurricanes and other disasters, home

insurers are pulling back from some U.S. coastal markets, warning of

gathering financial storm clouds over how the U.S. pays for the damage

of catastrophe. This development is another fallout of Hurricane

Katrina, whose mounting toll of destruction along the Gulf Coast has

precipitated a growing industry debate about the combined effect of

climate trends and population growth in coastal areas.

Seven

of the 12 costliest insured disasters in U.S. history occurred in the

past two years. At $57.7 billion, private insured losses in 2005 were

more than double those of 2004. Meanwhile,

government-provided crop and flood insurance programs are experiencing rising losses,

wildfire events are causing two times more damage compared to a few

decades ago and coastal erosion insurance is now entirely unavailable.[82]

In March 2006, catastrophe modeler Risk Management Solutions Inc. raised

its estimate of insurance losses this year by nearly 50% above pre-2004

baselines for the East and Gulf coasts. The company, whose estimates

are used by insurers to calculate premiums, blamed “higher sea surface

temperatures.”[83]

Rating agencies are putting large insurers such as Allstate and State

Farm on notice for possible ratings downgrades. Significant premium

increases, tightening terms and market withdrawals are sure to come

next. Companies are shedding homeowner’s policies and driving residents

to taxpayer-funded state insurance plans:[84]

-

Florida’s Citizens Property

Insurance Corp., for example, has 815,000 policyholders and is

adding 40,000 a month.

-

Poe Financial Group collapsed in

2005, and many of its 316,000 policyholders probably will move to

Citizens, which already faces a $1.7 billion deficit.

-

Since 29 August 2005, when the

Katrina hurricane hit along the Gulf Coast, Allstate Corp., the

industry's second-largest company, has ceased writing homeowners

policies in Louisiana, Florida and coastal parts of Texas and New

York State. They have stopped underwriting earthquake coverage in California and elsewhere.

-

Louisiana Citizens Property

Insurance Corp., the state’s last-resort insurer, expects to reach

200,000 policies this year; it had none in 2004. Texas’ insurer of

last resort says it is down to $1.3 billion in reserves and wants to

raise rates by at least 22%.

Homeowners are moving to state-backed insurer plans of last resort,

whose costs are rising. Taxpayers, who subsidize such plans, are

already feeling the impact. While Katrina caused an estimated $38-$50

billion in private insured losses, it also cost the federal flood

insurance program $50 billion and prompted federal relief spending of

more than $100 billion.[85]

That includes about $10 billion for Mississippi and Louisiana

homeowners.

Governments assume a considerable share of the exposures to the costs of

weather-related events. Requests for all forms of disaster relief

(including those for the agriculture sector) doubled between the

mid-1980s and mid-1990s and total federal disaster-related payments

amounted to $120 billion between 1993 and 1997. Federal aid for

Hurricane Katrina alone is anticipated to top $200 billion.[86]

Climate stresses will place more political and financial burden on

federal and local governments as they assume broader exposures and are

pressured to serve as insurers of last resort. Governments also are

compelled to address events for which there is no insurance at all,

while paying for disaster preparedness and recovery operations. For

example, federal and local governments are incurring substantial

liability and expenses due to landslides in southern California, with

losses averaging $100 million per year.[87]

Business and consumers will be burdened because cash-strapped

governments generally cap paid losses and shift greater portions of risk

back to consumers.

There

is a business case for aggressively moving to limit emissions of the

gasses that are changing the climate, and companies are implementing

it. Books like the international bestseller, Natural Capitalism

and a staggering array of others prove how the rapidly emerging best

practice in sustainable technologies can meet basic human needs around

the world and solve most of the environmental problems facing the planet

at a profit.

There

are enormous risks to companies and communities that do not participate

in such programs.

This

manual describes how your community can work with its business community

to enable citizens and companies to capture these advantages, and avoid

these risks.

|