|

Climate Protection Manual |

|||

HOME | SERVICES | CONTACTYOUR LOCATION: HOME >> Chapter 4: Set an Emissions Reduction Goal

|

||||

|

|

Chapter 4: Set an Emissions Reduction GoalEvery city that undertakes a climate protection program will need to set a target for reducing its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The targets cities set should be tied to the various scientific studies that calculate the amount of reductions necessary by various dates in the future. They should be as aggressive as possible while still being achievable. Some communities are ready to move rapidly to protect the climate; others will wish to move more slowly. The goal each city adopts will depend on how quickly it is ready to move.The below table of contents is "click-able" if you wish to jump to different sub-sections on this page.

| |||

Set an Emission Reduction GoalIntroductionThe debate is over. The science is in. The time to act is now. Global warming is a serious issue facing the world. We can protect our environment and leave California a better place without harming our economy.

-California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger[1]

Examples of Emission TargetsCities typically follow one of several approaches:

Establishing a Time Frame

Based on the best estimates by climate scientists at the time (1996) the Kyoto Protocol set the base date of 1990 as the level of carbon emissions to reduce below. Many cities have followed this lead. However, many jurisdictions will find that they were not keeping records of their carbon emissions at that time. Depending on the results of the baseline inventory process (see Chapter 3), and the community’s level of comfort with the accuracy of the baseline data of 1990 emission levels, there may be reasons to set a different point in time from which to measure carbon reductions.

Some jurisdictions have chosen goals that will reduce emissions from what they are at the time of goal setting:

Rather than establish 1990 or other historic baselines, cities such as Los Angeles and Berkeley, California established emission reduction goals compared to the emission levels expected from a “business as usual” projection of future emissions.

Set Aggressive Goals

Emission reduction pledges, such as those represented by the Kyoto Protocol and embodied in the Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement are a good start. However, increasingly clear scientific evidence of the speed and severity of global warming is eliciting calls from scientists and business and political leaders throughout the world for stronger actions than those called for by the Kyoto Protocol.

In 2000, the British Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution concluded that the U.K. needed to reduce carbon emissions by 60% by 2050. It stated that such a target would be needed to “prevent excessive climate change” by keeping levels of CO2 in the atmosphere below 550 parts per million (ppm).[13] The U.K. government formally adopted this goal. The Commission recommended a short-term goal of 20% carbon reduction by 2010. The government initially set this target, but recently scaled back to 15-18% reduction by 2010, as it struggles with the initial reluctance to change, and the difficulties of getting such a program underway.

Lacking a coherent national mechanism to limit carbon emissions, U.S. emissions increased 20% from 1990 to 2003,[14] despite the economy becoming about 20% less carbon intensive.[15] The U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts a 75% growth in global emissions from 2003 to 2030.[16] Observers around the world fear that unless the U.S. undertakes more aggressive reduction plans there will be little hope of controlling greenhouse warming.

In October 2006 a report commissioned by British Prime Minister Blair was released. Its author, the former Chief Economist of the World Bank, Sir Nicolas Stern, stated that the planet faces catastrophe unless urgent measures are taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[17] The Report stated that the world has the means to avert catastrophe from global warming although it will involve the huge expense of 1% of global GDP (£0.3trn). This may seem like an untenable amount of money to spend, but the report warned that if it is not done, global warming could cost the world's economies up to 20% of their gross domestic product (GDP). The report called for "a rapid increase in research and development of low carbon technologies”.[18]

The report warned that 200 million people are at risk of being driven from their homes by flood or drought by 2050. Four million square kilometres of land, home to one-twentieth of the world's population, is threatened by floods from melting glaciers. It observed that 35,000 Europeans died in the 2003 heatwave, an event likely to become 'commonplace'.

To prevent these and worse disasters, the report found, it would be necessary to spent £200bn, or 1% of global GDP every year. Failure to take such action to limit climate change, the report warned, would force the world’s economies to spend up to 20% of their GDP each year to deal with the floods, storms, fires, droughts and other catastrophes. The technology does exist to confront the challenge, the report stated, the financing public and private does exist, so it doesn’t have to be a catastrophe, but it’s a challenging message. In fact, the report finds reducing climate change could become one of the world’s biggest growth industries, generating around £250bn of business globally by 2050.

The Stern Report reckons that such aggressive action would enable “carbon dioxide levels to "stabilize" at 550ppm. This accords with scientists’ predictions that a 70-80% reduction of climate changing emissions from all sources will be needed to “stabilize” concentrations of GHGs in the atmosphere by the middle of the 21st century at approximately double pre-industrial levels of CO2 in the atmosphere.

Some scientists, however, fear that even these levels would be too high. They point out that the word “stabilise,” is misleading, however. Given the time lags in global climate, it will take at least another 50 years for the climate to stabilize at any particular level. There is intense debate between scientists about how high concentrations can rise before life as we know it cannot survive.

The level in the atmosphere of carbon dioxide, the principal greenhouse gas, stood at 280 parts per million by volume (ppm) before the Industrial Revolution, in about 1780. The level of CO2 in the atmosphere today stands at 382 ppm.

Without an unthinkable dislocation in present energy practices, concentrations of GHGs will inevitably reach 400 ppm in 10 years. Scientists believe that this is the upper limit that can be safely maintained. At a level of 450 ppm, the world would see a 4-5 F degree increase in temperature, an interference with the climate system that essentially all climate scientists consider dangerous.

The Stern report warned:

Global warming reinforces itself, and is now occurring must faster than had been predicted. Key factors include:

Most climate scientists thus agree that the goal should be to peak at the lowest level of emissions possible and then drop from there until the world reaches levels well be low pre-industrial concentrations.[20]

Examples of Aggressive Goals:

Recommended Process

The following process lays out a 15-step approach that cities may follow to undertake an initial goal-setting process.

Factors to Consider in Choosing a Goal

In addition to the variables described above, there are other factors to consider in setting a target for climate protection. These include:

Outcome-based goals:

MeasurementThree fundamental choices exist regarding how to measure greenhouse or climate change goals:

Primary Measurement StrategiesAll climate change goals will interact with population growth, economic development and emissions rates. A simple formula is:(Population) X (Per capita GDP) X (GHG intensity*) = total GHG emissions.[44]* GHG intensity is defined as GHG emissions per dollar of GDP generated in a given time period

Total emissions caps set the total amount of GHGs that can be emitted; the most meaningful measure is actual GHGs being put into the atmosphere. A goal or limit of total emissions can be achieved by reducing any or all of the three variables in the equation above. As described above, most cities and nations have adopted goals like the Kyoto Protocol that would limit total emissions. Total emissions goals are stronger than goals based on limits to carbon intensity or per capita limits.

Examples of total emissions limitation goals include:

Total emission reduction goals can be stated on a per capita basis. Sweden translated its overall emissions goal of 50% reduction from 2005 to 2050 into a per capita goal of achieving 4.5 million tons of CO2 emitted per person. Its emissions at the time were 8 million tons per capita.[46] To achieve its total emissions reduction goals, Sweden’s population will have to remain constant.

The U.S. government (as per policy statement by President Bush in 2002, not enacted into law) is aiming for an 18% reduction in carbon intensity from 2002-2012. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the U.S. economy has been steadily reducing its carbon intensity for the past two decades through energy efficiency, and through the steady transition of the U.S. economy from energy-intensive heavy manufacturing and light manufacturing to services during the past three decades.[47]

Per capita goals or intensity goals leave room for total GHG emissions to increase if the population or per capita GDP increase faster than the reduction of emissions per capita or GHG intensity.[48]

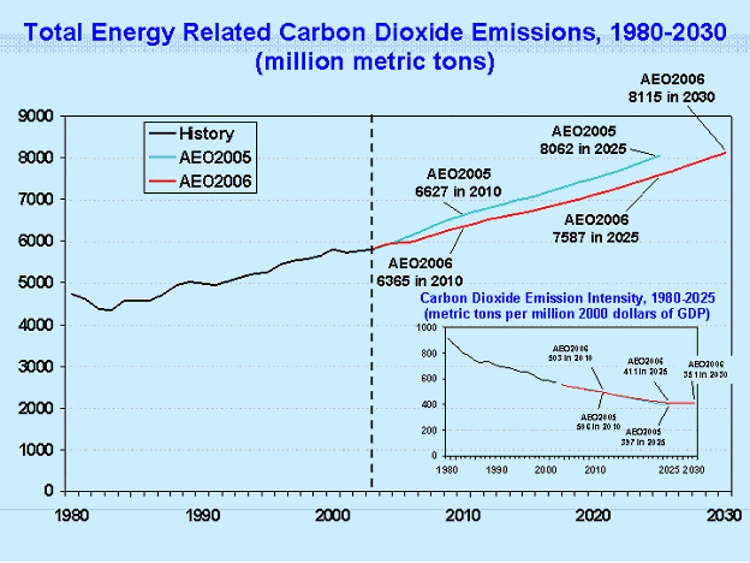

A decrease in intensity does not necessary mean a decrease in actual GHG emissions. As a measure of progress, carbon intensity must be used with caution. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) chart below illustrates that while U.S. carbon intensity is decreasing, actual GHG emissions are projected by EIA to rise significantly by 2030.

Figure: Energy Information AdministrationGross Emissions vs. Net or Aggregate EmissionsThough U.S. cities have generally chosen to set gross emissions goals (i.e. without subtracting for carbon absorption), the international reporting system established by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for the Kyoto Protocol recognizes an “aggregate” emissions reporting basis in which gross emissions are offset by credits for potential emissions absorption, for example, from tree planting. The U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol, upon which it is based, are aggregate emissions commitments.[49]

Carbon Only vs. All GHGsThe Kyoto Protocol recognizes and regulates six GHGs: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and perfluorocarbons (PFCs). The U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement represents a goal for “global warming pollutants,” meaning the six Kyoto GHGs. The reporting requirements of the Chicago Climate Exchange also include all GHGs converted to CO2 equivalents. These and most GHG reporting and goals call for the reduction of all GHGs; however, they convert measurements of the other gases to metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents (MtCO2e) in which the other five GHG emissions are converted to the equivalent amounts of CO2. This is a good practice. Capturing all GHGs is important because all the other GHGs have more warming potential of CO2. Thus, even smaller releases of these gases can have dangerous impacts on the climate. Doing this, however, requires more sophisticated measures of sources of emissions than just tracking fossil energy use.

Outcome-based Goals

Local and regional governments have increasingly been held accountable to specific outcomes, particularly with regard to environmental and health regulations. Stakeholder efforts since the early 1990s to create “progress,” “sustainability” or other quality of life indicators are based on the concept of identifying specific outcomes that the community wishes to achieve, and implementing management systems to ensure these outcomes. Climate change outcomes are no different. Good goals, policies and activities should be tied to consensus outcomes that are measurable and that contribute towards all of the positive outcomes the community desires. Climate stabilization and economic development are two primary goals that should drive your climate protection program.

Climate Stabilization: The Wedge StrategyAllowing emissions of GHGs to rise is risking the ability of the Earth to support life as we have known it. GHG levels now present in the atmosphere are unprecedented in human history and are increasing every day.[50] Given that our GHG emissions to date already have created climate instability, stabilizing emissions at approximately double the preindustrial level of GHGs in the atmosphere is likely to mean accepting a very different climate than we experience today, one about 4 to 5 degrees F warmer than in the year 2000. As stated in the science primer at the beginning of this chapter, that will result in enormous dislocations around the globe.

Even so, stabilization at some relatively safe level is widely agreed by scientists to be preferable to allowing a continued rise in atmospheric levels of GHGs that would mean temperature increases more than twice this great and the much greater instability this would bring.

Achieving stabilization may require setting far more aggressive goals than cities have done to date. It is better to start somewhere, even if it is an inadequate goal, than to set no goals at all. However, city leaders should prepare themselves and their citizens for the likelihood that far tougher standards will be necessary.The Carbon Mitigation Initiative at Princeton University approaches the climate change challenge as a choice between two scenarios. A business-as-usual (or do-nothing) scenario of continuing the historic growth of GHG emissions since 1976 to 2056, would lead to a tripling of atmospheric carbon from pre-industrial levels, with 14 billion tons of carbon added annually. The second strategy would hold annual carbon emissions at seven billion tons until 2056, then cut emissions in half for the following century to avoid doubling atmospheric carbon from pre-industrial levels.

The Princeton Carbon Mitigation Initiative[51] outlines 16 basic strategies (below) to achieve the stabilization strategy. Each of the strategies would result in the reduction of about a billion tons of carbon a year. To hold emissions at 7 billion tons annually the world would need to implement seven of the measures below. Reducing emissions further could be achieved by implementing more measures:[52]

End-user efficiency and conservation

Fuel switching (“power generation” and “alternative energy sources”)

Carbon capture and storage

Authors Socolow and Pacala[53] note that setting a price for carbon emissions between $100 and $200 per ton—enough to make it cheaper for owners of coal plants to sequester carbon rather than vent it—is required to “jump-start” the needed transition. The current price (as of January, 2007) on both the Chicago Climate Exchange and the European Exchange is running between $4 and $5. They also note that holding global population to eight billion rather than the projected nine billion would also be the equivalent of reducing emissions by one billion tons over forecasts, and would thus count as one of the seven strategies required.

Goals must also consider local and global issues of carbon equity (or environmental justice). These sorts of issues have been central to international climate change negotiations:

Economic Development

Since the 1970s, advocates for environmental health have demonstrated that well-designed environmental protection measures increase economic competitiveness.[55] Yet the climate change debates in the U.S. have featured unfortunate and acrimonious claims that economic competitiveness and growth would be unacceptably diminished by climate change efforts. The discussion in Chapter 2 of this manual shows that there is actually a strong business case for aggressively reducing emissions of GHGs. Based on reading the report on which Chapter 2 of this manual is based, the Chamber of Commerce of Boulder, Colorado switched from opposing a proposed municipal carbon tax to supporting it.A city’s discussions must examine all sides of the issue: the economic consequences of runaway climate change as well as the potential costs or benefits of responsibly addressing it. As the Stern Report in the UK found, the costs of doing nothing may far exceed any costs of action. The California Global Warming Solutions Act leads with a warning for other U.S. states and regions:Global warming poses a serious threat to the economic well-being, public health, natural resources, and the environment of California. Global warming will have detrimental effects on some of California’s largest industries, including agriculture, wine, tourism, skiing, recreational and commercial fishing and forestry.[56]

Predictions that climate change strategies would diminish economic health are largely based on the unexamined expectation that the only way to elicit reductions of energy use would be to require higher energy costs for businesses and consumers. However, as described by economic analysts at the non-profit research center, Redefining Progress:. . . credible economic models estimate that controlling U.S. emissions of greenhouse gases would result in less than a 0.5% one-time loss of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Public policies with significant impacts are usually phased in over time. Assuming a ten-year transition period, this approach would amount to reduced growth of GDP and real income of less than one tenth of 1% per year. Pessimistic studies estimate that real GDP per employee will grow from $54,000 in 1995 to $61,000 in 2010 under Kyoto Protocol commitments.[57]

Similar projections supported the U.K. government’s commitment to a 60% reduction goal by 2050.[58]

Nearly all climate change investments by the private sector (and public sector organizations through management of their own operations) actually achieve strong rates of return—far beyond the cost of money (the bottom-line of investment returns). These rates of return are amplified if fossil fuel energy prices increase faster than the rate of inflation. Unless a government is prepared to make the case that fossil fuel energy will decrease in real dollar costs (a very difficult case to make in a time of diminishing U.S. production and global reserves, increasing global demand and increasing availability of cost-effective substitutes), community policies that support reduced fossil fuel dependence will enhance your community’s economic competitiveness.[59]

Climate protection programs also confer economic development benefits. These include quality of life improvements and reduction of indirect costs (such as costs of traffic congestion) as well as increased job creation.

The U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement states:. . . many cities throughout the nation, both large and small, are reducing global warming pollutants through programs that provide economic and quality of life benefits such as reduced energy bills, green space preservation, air quality improvements, reduced traffic congestion, improved transportation choices, and economic development and job creation through energy conservation and new energy technologies. . .[60]

The economic development case was important to the Seattle Green Ribbon Commission’s 2006 findings and recommendations:One of the primary obstacles to responsible climate policy is the perception that reducing fossil fuel use will be economically costly. We believe the opposite is true. The road to a more climate-friendly community is paved with economic opportunities ranging from cost-savings for families to new business development for companies. For example, the state’s new “clean car” standards are projected to save drivers $2,500-$3,000 in fuel costs over the life of the vehicle, while reducing global warming pollution by 25-30% per vehicle. Similarly, investing in more energy efficient homes and businesses creates local jobs. And, here in Seattle, new jobs already are being created by climate-friendly businesses engaged in sustainable building design and biodiesel production.[61]

Other examples of governments including economic development goals in their climate change efforts are:

Additional Resources

|